The aviation industry is doing more than just bouncing back. It’s expected to soar even higher than before – and, with it, increase pressure for engineering and MRO (Maintenance, Repair, and Operations) teams.

The aviation industry is doing more than just bouncing back. It’s expected to soar even higher than before – and, with it, increase pressure for engineering and MRO (Maintenance, Repair, and Operations) teams.

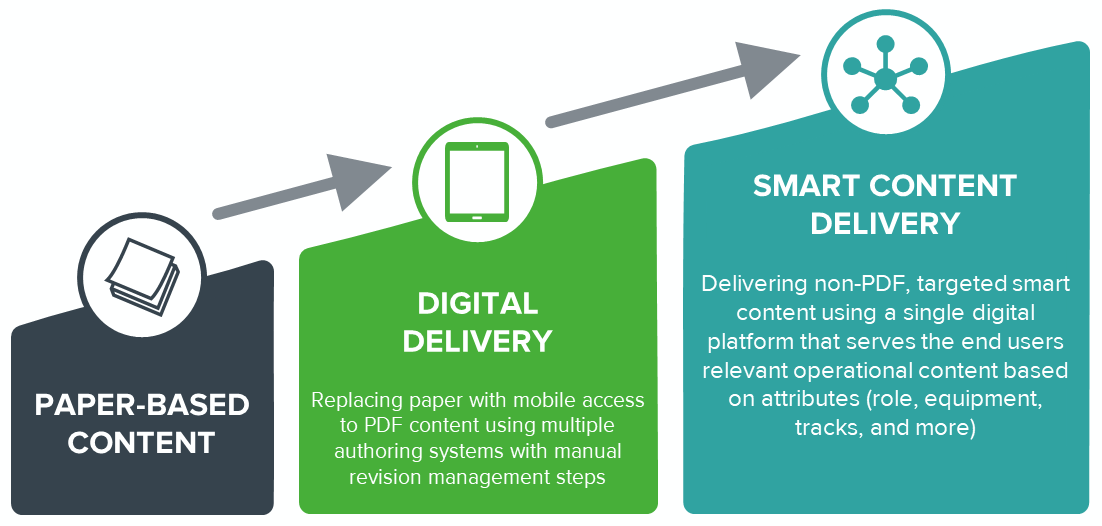

If your railroad’s paper-based operational documents are a thing of the past – now ready to become a collector’s item on eBay – congratulations! Digital transformation for rail’s paper-based grips, bulletins, timetables, general orders, rule books and manuals are a big accomplishment and should be celebrated.

But taking the next digital step is where even more value comes in.

First movers in rail experienced the cost reductions, efficiencies, and safety gains of digitizing documents. But the journey continues to a broader transformation – the era of smart content delivery.

If your railroad’s paper-based operational documents are a thing of the past – now ready to become a collector’s item on eBay – congratulations! Digital transformation for rail’s paper-based grips, bulletins, timetables, general orders, rule books and manuals are a big accomplishment and should be celebrated.

But taking the next digital step is where even more value comes in.

First movers in rail experienced the cost reductions, efficiencies, and safety gains of digitizing documents. But the journey continues to a broader transformation – the era of smart content delivery.

Comply365 has been partnering with rail operators to provide support at every step of their digital transformation journey, including delivery of smart content to engineers and conductors. In this Railway Age article, read more about three major initiatives where our technology is at the cornerstone.

Ready to learn more? Reach out to us for more details on how you can start delivering smart content to your mobile end users.

Comply365 has been partnering with rail operators to provide support at every step of their digital transformation journey, including delivery of smart content to engineers and conductors. In this Railway Age article, read more about three major initiatives where our technology is at the cornerstone.

Ready to learn more? Reach out to us for more details on how you can start delivering smart content to your mobile end users.

The years 2020 and 2021 will be remembered as the most turbulent period in the history of the airline industry, marked by unprecedented fluctuations in passenger volumes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Regaining passenger confidence has become a critical factor for airlines to navigate the ongoing economic challenges and remain competitive in the uncertain years ahead.

Emerging technologies, once sidelined during the previous decade of industry growth, are now being rigorously evaluated for their potential to address crucial COVID-19 challenges. Here are four key technology trends set to transform the aviation industry:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been pivotal in transforming aviation operations during the crisis. AI is being used to optimize flight routes, enhance weather forecasting, and develop virtual assistants for customer queries. Additionally, AI is improving logistics operations, facial recognition systems for security checks, and self-service kiosks with augmented reality.

According to a market survey, 97.2% of aviation companies are deploying big data and AI, with 76.5% leveraging collected data for cognitive learning initiatives. For instance, Southwest Airlines has partnered with NASA to use machine-learning algorithms for safety enhancements, while easyJet employs AI for predictive analysis to offer personalized traveler services.

The pandemic has underscored the need for frictionless travel, making biometrics a must-have technology. Star Alliance launched an interoperable biometric identity platform in November 2020, and Emirates introduced an integrated biometric path at Dubai International Airport. Etihad has also trialed facial biometric check-in for cabin crew, highlighting the industry’s shift towards seamless passenger experiences.

Airlines are increasingly aware of the limitations of legacy infrastructure, especially in delivering high-performance enterprise systems and customer-facing applications. A hybrid cloud infrastructure strategy is enabling airlines to scale resources dynamically to meet the demands of the digital age.

The cloud is now seen as the most secure and scalable solution for data management, such as document management for aircraft OEM data. Centralized databases reduce information silos, enhancing security and operational efficiency.

Sustainability is a critical focus in climate change discussions, with aviation being a significant contributor to fossil fuel consumption and environmental impact. The pandemic has accelerated the push for decarbonization and green technology investments. Companies like IAG, Japan Airlines, and Qantas are committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, while Finnair aims for carbon neutrality by 2045. Digitization is playing a crucial role in facilitating these sustainability goals.

The benefits of technology in operations, cybersecurity, and customer experience are already evident and will continue to grow. 2021 marks the era of accelerated digital transformation, with technology becoming an integral part of everyday life across all industries, especially aviation. Airlines must embrace these advancements to enhance their services, gain a competitive edge, and avoid being left behind in the digital revolution.

In aviation, practical drift refers to the gradual deviation of actual performance from designed performance due to factors that may or may not be under an organization’s direct control. This phenomenon can significantly impact an airline’s safety management system. According to ICAO, practical drift is inevitable, primarily due to human factors. However, with robust processes, data analysis, and a strong safety culture, organizations can harmonize these deviations and prevent catastrophic outcomes.

Accidents and serious incidents in aviation often result from a combination of seemingly minor, unrelated issues. These latent issues can remain undetected until they converge unexpectedly, leading to a major problem. Practical drift exacerbates these risks by gradually eroding the effectiveness of safety controls.

Key contributors to practical drift include:

By conducting meaningful trend analysis on routine operations, organizations can identify and address these latent issues before they escalate.

A drift diagram visually represents the gradual deviation of operational performance from the baseline (ideal) performance. Initially, systems are designed to follow a straight-line performance trajectory (blue line). However, real-world operations often deviate from this baseline due to external influences, resulting in a “practical drift” (red line).

Figure: A drift diagram showing baseline performance (blue) vs. actual performance (red) over time.

Scott A. Snook, who first proposed the theory of practical drift, argues that drift is inevitable in any system. Organizations must proactively monitor and analyze data to identify leading indicators of drift and implement corrective actions.

To combat practical drift, aviation organizations should:

Aircraft drift—a term often used to describe deviations from intended flight paths—can be influenced by practical drift. For example, outdated technology, procedural gaps, or complacency among pilots can lead to unintended deviations. Understanding the relationship between practical drift and aircraft drift is essential for enhancing aviation safety.

Practical drift is an inherent challenge in aviation safety management. By recognizing its causes, leveraging tools like drift diagrams, and implementing proactive mitigation strategies, organizations can reduce risks and maintain operational excellence. Stay vigilant, analyze trends, and foster a culture of continuous improvement to keep your operations on course.

While the specifics may vary slightly from one organization to another, the core principles of an aviation Safety Management System (SMS) remain consistent. These four components (which in turn are broken down into twelve elements) are listed in ICAO Document 9859 and it is likely that you are already familiar with them, particularly if you have implemented your own SMS by now.

The following article examines how each of these four components should be developing in your organization by asking a number of questions that might be phrased by your NAA inspectors as they seek to determine if your SMS is delivering your stated safety objectives and is improving continuously as part of the Performance Based Oversight objectives discussed in Annex, Revision 1.

These three questions apply across the entire organization and are not confined to Flight Operations. This can only be achieved if management are likewise engaged and empowered to deliver the safety policy. What evidence is available to demonstrate your enterprise approach to safety management? Items such as an increase in voluntary reporting rates for all departments can be used. Furthermore, the establishment of a Just Culture (ASAP in the USA) must be evidenced and must be used by management at all levels.

A primary objective of the risk control process should be to ensure that the appropriate resource is allocated to mitigate identified risks. Ideally, a register of all controls should be maintained alongside the risk register. All identified risks must be accepted by a responsible manager and high-level decisions should be made using risk-based analysis. Finally, there must be suitable processes in place to review and monitor all risks listed in the register as part of the assurance processes.

Assurance is a critical component of an SMS. Safety Performance Indicators (SPIs) and Safety Performance Targets (SPTs) are typically used to meet these requirements, as detailed in Document 9859 (Issue 4). Without these, it’s challenging to demonstrate ALoSP and continuous improvement.

Unless the safety policy and its objectives are communicated widely and in a format that is designed to engage all employees, it is unlikely to be effective. Poster campaigns can be useful, but short lived. Management must promote the safety policy continuously. This could be in the form of monthly safety newsletters by fleet managers (which could be a leading SPI if used). Again, this process should be adopted across all departments and whilst safety promotion is often very good in the flight operation:

The quotation below is by William Voss (past CEO of the Flight Safety Foundation). It encapsulates how an effective SMS should function and also demonstrates the need for good safety promotion across an organization:

“Go back to last year’s budget and see if you can find one single instance where information from your SMS caused you to spend money differently to how you had planned. If you cannot find an example of that in your operation you either have an extraordinarily brilliant budgeting process or your SMS is not delivering. I would bet on the latter.”

To ensure that your organization implements an effective safety management system, you need to be able to continuously monitor each aspect of your system and question whether your implemented processes are as effective as they could be.An effective SMS goes beyond these four principles. It encompasses numerous aspects that airlines must consider to ensure safety and compliance.

In November 2019, revision 1 to ICAO Annex 19 became extant. Consequently, your regulator is likely to start taking a deeper interest in your Safety Management System. Specifically, the need to demonstrate continuous improvement in safety and to show how you are achieving your stated safety objectives will come under increased scrutiny. This is because ICAO will start to audit NAAs to determine their compliance with the new Annex 19 which, in turn, will result in them taking a keener interest in your SMS. How you go about demonstrating that you are meeting these emerging requirements starts with your organisation’s safety policy and its objectives.

Progress made in the achievement of stated objectives should be monitored and reported on a regular basis. This is accomplished through the identification of safety performance indicators (SPIs), which are used to monitor and measure safety performance. Through the identification of SPIs, information obtained will allow senior management to be aware of the current situation and support decision- making, including determining whether actions are required to further mitigate safety risks to ensure the organisation achieves its safety goals.

The generic safety performance management process is shown below in figure 1 (source: ICAO Document 9859)

Safety data is entered into the process via the Safety Data Capture and Processing System (SDCPS). By using appropriate analysis techniques, the captured safety data can be turned into useful information that can then be used to monitor the organisation’s safety performance. This is achieved by the establishment of appropriate safety objectives and their associated safety performance indicators (SPI). Additionally, captured and analysed safety information will allow management to identify any actions required to maintain a safe operation.

Unless the safety performance management process is communicated to the entire workforce, it will fail to meet its objectives. The safety promotion aspect cannot be overstated, it is vital that all personnel across all departments are informed and engaged in this important process.

Safety performance management helps the organisation to ask and to answer the four most important questions regarding safety of their operation:

Safety objectives are the starting point for safety performance management systems. They are brief, high-level statements of the desired safety outcomes to be accomplished. Safety objectives provide direction to the organisation’s activities and should therefore be consistent with the safety policy that sets out the organisation’s high-level safety commitment. They are also useful to communicate safety priorities to the workforce. Establishing safety objectives provides strategic direction for the safety performance management process and provides a sound basis for safety related decision-making.

Safety objectives may be:

As a general guide, safety objectives should be based on SMART criteria: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-Bound; e.g. Increase the number of voluntary, safety reports by 100% over the next 4 years. Additionally, a mix of process and outcome objectives should be determined. When senior management define an organisation’s safety objectives, they need to consider the size and complexity of their operation and also the past performance in terms of safety. For example, management may already be aware of a number of areas of concern such as an increased number of runway incursions. The safety objective could be either process orientated such as the establishment of local runway safety teams at each airport in the next year or it could be outcome oriented e.g. a reduction in runway incursions from 10 every thousand movements to 2, over the next 12 months.

In order to monitor progress towards achieving the stated safety objectives, an organisation must develop a means to measure performance towards these goals. This is usually in the form of Safety Performance Indicators (SPI). SPIs provide management with an overview of how well the organisation is progressing in achieving its stated safety objectives. There are a number of different types of SPI that could be considered (all are equally valid):

It is important that, when setting SPIs, they are aligned with the organisation’s safety objectives. Furthermore, a mix of leading and lagging SPIs should be used. Primarily, quantitative SPIs will be used because they are easier to monitor and ultimately present during management meetings. Of most importance is that SPIs provide decision makers with relevant safety information such that any decisions made are based on reliable and defensible data. Furthermore, well thought out SPIs will allow for the development of meaningful Safety Performance Targets that will show progress towards the achievement of stated safety objectives.

When defining their SPIs, organisations should try to introduce a mix of leading and lagging indicators. However, the two types of SPI should not (if possible) be defined in isolation. There should be some form of link between the leading SPI and the lagging SPI. This is best explained by reference to the diagram at figure 2 (source: ICAO Document 9859).

Figure 2 shows the relationship between leading and lagging indicators. Of note is the fact that the main SPI (Number of runway excursions/1000 landings) is supported by two other SPIs. There is a leading SPI that accounts for the number of pilots who have received formal training in the issue. Additionally, the organisation has identified that a primary cause of runway excursions is unstable approaches. With this in mind, they have set this as an SPI which will serve as an indicator towards the primary event. These “indicator” issues are often referred to as “pre-cursor events”.

It is important that, when setting SPIs, they are aligned with the organisation’s safety objectives. Furthermore, a mix of leading and lagging SPIs should be used. Primarily, quantitative SPIs will be used because they are easier to monitor and ultimately present during management meetings. Of most importance is that SPIs provide decision makers with relevant safety information such that any decisions made are based on reliable and defensible data. Furthermore, well thought out SPIs will allow for the development of meaningful Safety Performance Targets that will show progress towards the achievement of stated safety objectives.

The contents of each SPI should include:

To support your SPI dashboard it is essential that the right safety management system software is in place. A well-designed and supported SMS software solution will help safety managers obtain information and data that can support their respective safety management priorities, and thereby provide the wider organisation with a set of SPIs that can be measured and monitored regularly. It will result in a safer airline organisation.

Note: Information in this article is taken from ICAO Document 9859.

To align with ICAO Annex 19 many aviation industry organisations will have implemented a Safety Management System (SMS) of some description by now. This requirement was first muted in the initial edition of ICAO, Annex 19 which became applicable in November 2013. This first issue set the groundwork for each participating country to establish a State Safety Program (SSP) which, in turn, would require all service providers to implement a SMS. The implications of the revised Annex 19 are, however, more widespread. Read the rest of the article to learn more about three particular implications.

The second edition of Annex 19 was issued in July 2016 and is set to become applicable in November 2019. As part of this edition, the requirement for SMS implementation is extended to include organisations involved with the type design and/or manufacture of aircraft engines and propellers.

As with the first issue of Annex 19, ICAO have updated their Safety Manual (ICAO Document 9859) to Edition 4. This important document provides an expansive explanation of the requirements contained in Annex 19. Of note are the emerging requirements for organizations to implement safety data collection and processing systems alongside data analysis tools and suitable presentation applications such as safety dashboards.

Organisations will also be expected to determine, and monitor, a series of Safety Performance Indicators (SPIs) with their accompanying targets. These SPIs will be specific to each organisation but should be aligned to their safety policy and objectives. Examination of SPIs and their targets coupled with enhanced data analysis and presentation techniques will enable Data Driven Decision Making (D3M).

Many aviation occurrences have resulted, at least in part, from poor management decisions, which can result in wasted money, labour and resources. In the short term, the goal of safety decision-makers is to minimise poor outcomes and achieve effective results, and in the long term, contribute to the achievement of the organisation’s safety objectives.

A structured approach such as D3M will drive management to making decisions based on what the safety data is indicating. This requires trust in the safety performance management framework, if there is confidence in the Safety Data Collection and Processing System there will be trust in any decisions derived from them.

ICAO is keen that organisations are able to make management decisions based on reliable and comprehensive safety data using D3M processes.

Regulators themselves will also be required to implement changes with respect to the new version of Annex 19. Specifically, they will be required to determine which sections of their jurisdiction require more detailed supervision as part of the Performance Based Oversight (PBO) requirements.

In effect, ICAO will require regulators to apportion their limited resource to those areas that require the most attention. The primary means by which an organisation can demonstrate to their regulators that they are meeting their safety targets and maintaining an Acceptable Level of Safety Performance is by suitable presentation of their SPIs and evidenced D3M. Can your current systems achieve this?

Finally, it is worth noting that ICAO have stated that they intend to commence an audit program of all NAAs to determine their compliance with Revision 1 of Annex 19. This audit program was due to start in 2018 but is likely to be delayed until next November 2019 to coincide with the activation of Annex 19, revision 1.

If your regulator has not been overly strict with the enforcement of ICAO SARPs with respect to SMS implementation; you can expect a sudden change of gear next year!

Having spent a great deal of time and effort in establishing your organisation’s Safety Management System (SMS) it is now perhaps worth examining if it is functioning as first envisaged.

There are a number of reasons why a SMS might not deliver exactly what was first hoped for and as part of the ICAO requirement to ensure continuous improvement you should conduct a detailed analysis of your system to determine any potential shortfalls. Furthermore, revision 1 to ICAO Annex 19 is scheduled to become applicable on 7th November 2019 and this latest issue contains further requirements on both State Safety Programs (SSP) and service provider SMSs.

This article will focus on five of the main reasons why a SMS might not perform as expected or meet emerging requirements in the near future:

The above list is far from exhaustive, but it does highlight some of the more common issues that organisations experience when establishing their SMS. A common theme is poorly thought out software support. Unless your chosen provider understands the emerging requirements that will become extant in November 2019, it is likely that your SMS will fail to meet the standards needed to satisfy your regulator. Furthermore, your management decision-making capability might not be focused in the appropriate areas to result in enterprise wide, improving safety performance.

Both A350 and B787 Dreamliner are swiftly becoming the world’s most technologically advanced airplanes, produced respectively by Airbus (Europe) and Boeing (USA).

But what makes these rival aircrafts so revolutionary? Here are some comparative features to get you thinking:

The 787 and A350 are the first large commercial aircraft to be constructed extensively from carbon fibre reinforced polymer (CFRP). CFRP is more durable as it doesn’t corrode to the same extent as traditional aluminium used in older planes, translating into lower maintenance costs for airlines.

The use of CFRP and other composites help the A350 and the 787 to be lighter than its predecessors. This, combined with unparalleled engine efficiency, make the overall cost of flying cheaper than before. The newer engines on both the A350 and 787 provide up to 25% improved fuel efficiency and 15 % less CO2 compared to older generations.

Both the 787 and the A350 have far quieter cabins than conventional aircraft, thanks to engine design developments from Rolls Royce and GE. The A350 specifically has the quietest cabin of any twin-aisle aircraft, with a typical noise level of 57 decibels – around the same as a normal conversation.

The 787 and the A350 have impressive range, both planes can travel at least 15,000 kilometres without stopping – The same as travelling from London to New York 2.5 times without stopping to refuel. This astonishing range is why airlines are now deploying the 787 and A350 on the world’s longest routes.

With all these benefits, both the Airbus A350 and Boeing 787 are without a doubt revolutionary in their design. However, as such, aircraft designs have become increasingly complicated and require constant review and updates to ensure safety, reliability and utility.

Learn how our leading document management solution, DocuNet can help your publishing department to manage increasingly complex Airbus and Boeing documents.

The Airbus A350 XWB has revolutionized modern aviation since its commercial debut three years ago. With over 142 deliveries to 17 global airlines, including Iberia and British Airways, the A350 is a game-changer.

But what makes this aircraft stand out? Here are 10 key facts about the Airbus A350 and why document management is critical for new fleet operations.

Introducing a new fleet like the Airbus A350 requires meticulous planning, especially when it comes to document management. From operational efficiency to compliance and safety, managing Airbus manuals is a complex but essential task.

A robust document management system simplifies the process, ensuring your manuals are updated accurately and efficiently. By leveraging the right tools, airlines can maintain compliance, reduce risks, and keep their fleets ready for takeoff.

The Airbus A350 combines cutting-edge technology, fuel efficiency, and passenger comfort, making it a top choice for airlines worldwide. However, successful fleet integration relies on effective document management to ensure operational readiness and compliance.